Hanover Township

Contents

Early Settlement

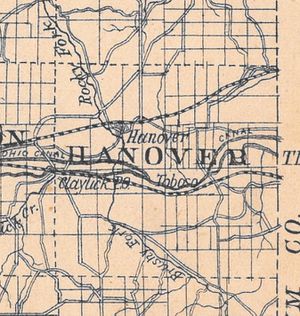

The township was one of the first areas settled by Europeans, seeing its first White explorer in the 1750s. Christopher Gist travelled along the Licking River through the township in 1751 [3] The first permanent settler—Philip Barrack, sometimes spelled Barrick—arrived in 1802. Barrack, who later ran a distillery and a brewery, was quickly followed by a number of other settlers. This influx to the population led to the early formation of the township in 1808. [4] Hanover, with its geographic placement, was the entry point for many early European settlers to the county. This was amplified by the eventual presence of three important transportation features in the township: the Canals of the Ohio and Erie System, the Interurban, and the railroads. Despite the early influx of people at the start of the nineteenth century, the first settlement in Hanover Township, called Boston, was not established until 1832, when a man named John Hoyt established a grocery between Nashport and Newark. A collection of houses followed, but would prove stagnant as the railroads and other transportation routes passed around the settlement. [5]

Toboso

The village of Toboso was established in 1852 by a leading county citizen and former congressman, William Stanbery. Stanberry hoped that the close proximity of the Ohio and Erie Canal, as well as a rail line, would turn the settlement into a thriving community. A post office was established in 1854 and remained open until 1857. The village remains along the Licking River as an unincorporated settlement with several streets of houses and a couple of churches. [6]

Old Hanover and Hanover

The township's largest settlement, also named Hanover, was officially founded in 1852 as well, but had previous settlement and iterations. The first permanent settler at the site of the future village was the same John Hoyt that had built a grocery at Toboso. He repeated this grocery business model along the Rocky Fork near the future site of Hanover in 1835 [7] The grocery store would anchor what grew became a small village. A plan for a village was laid out on the property of John Hollister in 1849 and named after a co-investor in the venture, John Fleming. Fleming would exist only until 1852, when the desire for a post office forced the villagers to choose a different name for the settlement. In 1852, the village gained its post office and a new moniker, Hanover. [8]

With its later start, Hanover was among the smaller villages in the nineteenth century, reaching only 314 residents by the 1900 census. [9]

The construction of nearby Dillon Dam in Muskingum County along the Licking River, would forever change the village of Hanover and the people who lived there. Flooding became an increasing danger to the Hanover area in the middle of the twentieth century, with a devastating flood striking Licking County in January 1959. [10] The federal government and the state worked to build a series of dams along the Muskingum Watershed, including Dillon Dam. This project, which spanned more than thirty years, would lead to the relocation of the village of Hanover from the banks of the Rocky Fork to an elevated position roughly one-quarter mile north of the previous site, which became known as "Old Hanover." The relocation was contentious. Monetary compensation for property losses assuaged some resident, but what was viewed as inadequate compensation for the construction of a new school, left some upset with the project and process. [11]

Blackhand Gorge State Nature Preserve

Black Hand Gorge Nature Preserve is part of a larger geological formation of sandstone in central Ohio known as the Black Hand Formation. This layer of rock permitted the development of the cliffs and narrows that provide such striking views in the region. [12] The formation and the gorge derived their names from a peculiar image that once appeared on the cliff face along the Licking River – The Black Hand.

The Black hand stone was a large carving that had the appearance of a hand and wrist with thumb and fingers extended. It's location was located a short distance upriver from Toboso. There is a legend—possibly indigenous but most likely springing from stories told by European settlers—on the origins of such a striking depiction. Whether the Black Hand was a natural coloration of stone or a ancient native American petroglyph is unknown, and will never be known; the Black Hand, along with the cliff face it was attached to, was destroyed during the construction of the Ohio and Erie Canal. Its name and its legends are all that remain to us. The Canal path joined the Licking River for a short distance in Hanover Township. What was typically a stand-alone waterway merged with the river near Toboso and exited south of Old Hanover. Locks, dams, and aqueducts were built along the canal's course and this affected the flow of the River. Obstructions, such as the cliff with the Black hand, were destroyed and removed. Though the canal had ceased functioning by the early 1900s, pieces of its infrastructure still stand in the Black Hand Gorge area. [13] The township's other transportation projects—the Interurban and Railroads—also left their mark on the Gorge.

The contemporary nature preserve that now encompasses a large portion of the "Narrows" of the Licking River was established in 1975. It comprises 956 acres that stretches along the Licking River from the eastern point of Toboso until the juncture of Brownsville Road and Brushy Fork Road south of Marne. The state-run property features biking along Blackhand Trail and five additional hiking trails. It preserves the natural beauty of the area, as well as the historic remnants of the Canal and Interurban lines.

For more information see also:

Aaron Keirns. Black Hand Gorge: A Journey Through Time. Howard, OH: Little River Publishing, 1995.

Harry B. Scott and Karl J. Skutski. The Hanover Story: The Saga of an American Village. Ann Arbor, MI: Braun-Brumfield, 1972.

Licking Valley Heritage Society website - http://www.lvheritage.org/

J.G.

Return to Townships and Communities main page.

References

- ↑ Hill, N., History of Licking County, (1881), 458-459

- ↑ Mills, W., Archaeological Atlas of Ohio, (1914), 45-46

- ↑ Hill, N., The History of Licking County, 206-208

- ↑ Combination Atlas of Licking County, Ohio, (1875), 29

- ↑ Ohio Ghost Towns: No 44 Licking County, ed. Helwig and Helwig, (1998), 41

- ↑ Ohio Ghost Towns: No 44 Licking County, ed. Helwig and Helwig, (1998), 149-150

- ↑ Brister, E., Centennial History, 255

- ↑ Ohio Ghost Towns: No 44 Licking County, ed. Helwig and Helwig, (1998), 73

- ↑ Brister, E., Centennial History, 248.

- ↑ "Newark Lashed by Raging Flood," The Newark Advocate, Jan. 22, 1959, 1

- ↑ Scott and Skutski, The Hanover Story: The Saga of an American Village, (1972), 9-11; Dell, G., "After Dillon...County Left Legacy of Trash, Junk," The Newark Advocate, Oct 31, 1964, 15; Massa, P., "Advocate Salutes Hanover," The Newark Advocate, Jul. 8, 1965, 1

- ↑ Brister, E., Centennial History, 78-79; https://stateparks.com/blackhand_gorge_state_nature_preserve_in_ohio.html

- ↑ Keirns, A., Black Hand Gorge: A Journey Through Time, (1995), 13-31