Difference between revisions of "Canal System in Licking County"

(→Canal Tales) |

|||

| (42 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==The Ohio and Erie Canal== | ==The Ohio and Erie Canal== | ||

| − | The Ohio and Erie was an important component of early American transportation and commerce. Though it thrived in a relatively short period of time, sometimes with barely 20 years of heavy activity in the 1830s and 40s, the canals that connected the great American waterways—from the Great Lakes to the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers--permitted economic expansion and settlement of important regions of the United States in an era before the widespread use of rail. <ref> Coleman | + | The Ohio and Erie was an important component of early American transportation and commerce. Though it thrived in a relatively short period of time, sometimes with barely 20 years of heavy activity in the 1830s and 40s, the canals that connected the great American waterways—from the Great Lakes to the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers--permitted economic expansion and settlement of important regions of the United States in an era before the widespread use of rail. <ref> Coleman, R., "Once a Great Notion," ''Ohio'', (August 1988), 18 </ref> The growing yet sparsely populated states West of the Appalachians and East of the Mississippi were rich in agricultural potential, but lacked the infrastructure to move goods and people quickly. A spike in the price of agricultural products in the 1820s provided the impetus to states like Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Indiana to begin ambitious canal-building projects to connect those important waterways to the towns and cities in the interior and far-flung coastal markets. After the passage of legislation on February 4, 1825, the Ohio-Erie Canal could begin construction. |

| − | The first groundbreaking took place at the Licking Summit near Newark on July 4th of that year. It was quickly joined by other canal construction sites in Ohio as the system's orchestrator, Alfred Kelley, sought to complete the canal as quickly as possible. Though it took 8 years of toil and just over $4 million dollars | + | The first groundbreaking took place at the Licking Summit, near Newark, on July 4th of that year. It was quickly joined by other canal construction sites in Ohio as the system's orchestrator, Alfred Kelley, sought to complete the canal as quickly as possible. Though it took 8 years of toil and just over $4 million dollars, the Ohio Canal System connected Lake Erie to the Ohio River in less time and at less cost than some of its neighboring states, finishing six months ahead of schedule in January 1833. <ref> Coleman, R., "Once a Great Notion," ''Ohio'', (August 1988), 23-24 </ref> The canal that stretched 333 miles of watery highway from Cleveland to Portsmouth included 152 locks, 16 aqueducts, and 153 culverts. The aqueducts were a clever feature of Ohio's canal system, permitting the canal to pass over the many existing small streams without disturbing their natural flow. |

| − | At its peak in 1851, before the increasing | + | At its peak in 1851, before the increasing competition of the railroads precipitated its decline, around 400 boats passed through the Ohio Canal System, generating about $350,000 in revenue. <ref> Jones, L., "Trace the Path of the 'big ditch'", ''Community Booster East'', Jul. 20, 2003, 9 </ref> Toll collectors along the path of the canal charged tolls and water rents to the captains based on their boat and the value of its cargo. Charges to use the canal could run two to three cents per mile and the average canal boat could carry from fifty to eighty tons of cargo in addition to crew and passengers. <ref> Brister, E., ''Centennial History of the City of Newark and Licking County, Ohio'', (1909), 183 </ref> |

| − | The massive undertaking also had a human cost; the hard-pressed canal builders, mostly Irish immigrants, suffered from low pay, poor work conditions, and outbreaks of debilitating | + | The massive undertaking also had a human cost; the hard-pressed canal builders, mostly Irish immigrants, suffered from low pay, poor work conditions, and outbreaks of debilitating diseases such as malaria, smallpox, and cholera. <ref> Pressler, C., "The Ohio Canal," ''The Advocate'', Nov. 6, 1983. For a counter to the poor pay and work conditions see Brister, E., ''Centennial History of the City of Newark and Licking County, Ohio'', (1909), 178-179. </ref> |

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

==The Canal in Licking County== | ==The Canal in Licking County== | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:Wiki KirkersvilleCoveredBridge.jpg|thumb|The Kirkersville Bridge over the Kirkersville canal feeder]]There were a number of canals constructed in Ohio and surrounding states during the 1820s and 1830s, and Licking County was the location of a critical stretch of the Ohio-Erie Canal, including the Licking Summit, which was the point of initial groundbreaking and, at 413 feet above the level of the Ohio River, was one of the points of highest elevation on the Canal. |

| − | A boat passing from Cleveland to Portsmouth would cross the county from the center of its eastern border | + | A boat passing from Cleveland to Portsmouth would cross the county from the center of its eastern border to exit in the southwest corner. Entering at Toboso, the canal moved west along what is now Ohio 16 to Newark. A boat would pass south of Newark's city center, near Market street or what is now Canal Street. Leaving Newark along Main St, the canal turned south along Union St. to what was once the separate village of [[Lockport]] and followed a southwestern course through what is now Heath and Ohio 79. The canal passed through Hebron and by Buckeye Lake—which would play a critical role as a reservoir—and exited the county near Millersport. Several feeder canals, or short additions to the system, were added at Kirkersville, Granville, Raccoon Creek, and the North Fork. |

| − | A groundbreaking ceremony took place in Newark on July 4th, 1825, with the Governors of Ohio and New York, as well as a number of other dignitaries, in attendance. Poor weather, a | + | A groundbreaking ceremony took place in Newark on July 4th, 1825, with the Governors of Ohio and New York, as well as a number of other dignitaries, in attendance. Poor weather, a trouble-ridden presentation, and a swarm of unhelpful flies allegedly made the party less than memorable, though the speeches given to inaugurate the event were recorded for posterity in local papers. <ref> Pressler, C., "The Ohio Canal," ''The Advocate'', Nov. 6, 1983 </ref> . |

| − | The | + | The topography of Licking County required a special excavation in the southern part of the county. This excavation, locally referred to as the "Deep Cut," incised through a ridge of earth along three miles of the canal route. At the deepest point, the laborers dug thirty-four feet down at an average depth of twenty-four feet, creating what was one of the largest projects undertaken in the canal's construction. <ref> Brister, E., ''Centennial History of the City of Newark and Licking County, Ohio'', (1909), 179 </ref> . |

| − | The transformation of Buckeye Lake was another local consequence of the canal; reserves of water were needed to maintain water levels in the canal system, particularly at the crucial point of the Licking Summit.<ref> Pressler, C. | + | The transformation of Buckeye Lake was another local consequence of the canal; reserves of water were needed to maintain water levels in the canal system, particularly at the crucial point of the Licking Summit.<ref> Pressler, C., "The Ohio Canal," ''The Advocate'', Nov. 6, 1983 </ref> Local water supplies were used when possible, but reservoirs and artificial lakes were used in their place if natural water systems proved insufficient. An area of shallow water and swampy wetlands along the South Fork of the Licking River, known as the "Big Swamp," was one natural geographic feature found by early European settlers and surveyors in central Ohio. This low-lying wetland, also known as the "Big Pond," became a reservoir known as the Licking County Reservoir in the 1830s with damns installed to increase the water level to a point sufficient for the use of the canal. The conversion of the area into Buckeye Lake led to increased economic activity for communities surrounding the new reservoir. <ref> Hall, L., ''The Advocate'', Feb. 12, 1984 </ref> |

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:Davidshaihouse 1875 atlas.jpg|thumb|Image of Davis-Shai House, or Davis-Armstrong House, included in 1875 Atlas of Licking County Ohio. The Ohio-Erie Canal is depicted in the foreground.]] |

| + | One citizen of Newark, Louella Fant, gave a vivid account in 1934 of the colorful scene and expectant crowds along the canal, reminiscing of the times when a boat would pass through town: "Men lolling on top of the cabin, women, and children dressed in calico dresses and sun-bonnets, or better clad in silk, with shawls about their shoulders with dainty lace and straw bonnets kept in place by a ribbon tied under the chin, occupied the chair on the deck and held sunshades to display the up-to-date fashions, as is always the fashion. Pretty faces often appeared at the windows. Persons on board ogled the natives—called to them in banter, others 'viewed the landscape o'er' with contempt or dropped the slant of the sun shades. " <ref> Jones, B., "Our County History," ''The Advocate'', Mar 5, 1934 </ref> | ||

| − | There are several factual, first-hand accounts of the Ohio-Erie canal in Licking County that lend themselves to an idyllic, romantic image of the experience. The reality may have been far messier and rougher | + | There are several factual, first-hand accounts of the Ohio-Erie canal in Licking County that lend themselves to an idyllic, romantic image of the experience. The reality may have been far messier and rougher than the stories indicate. In its final years in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the canal in Newark proved to be a health hazard and open sewer. |

==Canal Tales== | ==Canal Tales== | ||

| + | The first canal boat built south of Cleveland may have been built in Licking County. E.M. P. Brister, in his ''Centennial History of the City of Newark and Licking County, Ohio'', credited the Troy and Ohio Line and the supervision of a Mr. Wallace with the construction of a boat at the warehouse built on the Granville feeder canal. <ref> Brister, E., ''Centennial History of the City of Newark and Licking County, Ohio'', (1909), 183 </ref> . | ||

| − | "The Licking Summit " was another canal boat built in Licking County, whose story survives due to its spectacular failure as a working boat; constructed in Hebron as an investment venture by local businessman led by Joshua Smith, the "Summit" set out on its maiden voyage on July 4th, 1828 to great fanfare. Much to the chagrin of the owners and passengers, the | + | "The Licking Summit " was another canal boat built in Licking County, whose story survives due to its spectacular failure as a working boat; constructed in Hebron as an investment venture by local businessman led by Joshua Smith, the "Summit" set out on its maiden voyage on July 4th, 1828 to great fanfare. Much to the chagrin of the owners and passengers, the "Summit" ran aground a few times on that first trip, and once it reached the gates of the lock at the Licking Summit, the boat proved too wide to pass through the canal locks. Unable to function as a canal boat, the "Summit" returned to Hebron where it remained tied in place on the water and became used as a saloon, and--allegedly--a house of prostitution. <ref> Hill, N., ''History of Licking County'', 598; Pressler, C., "The Ohio Canal," ''The Advocate'', Nov. 6, 1983 </ref> The boat may also have been called "The Lady Jane" at some point during its existence. Joseph Simpson, who collected a number of stories along with his first-hand accounts in ''The Story of Buckeye Lake,'' claimed the "Lady Jane" as the original name of the boat and provided a story that mirrors other accounts. <ref> Simpson, J.'' The Story of Buckeye Lake: Historical,'' (1912), 35-38 </ref> |

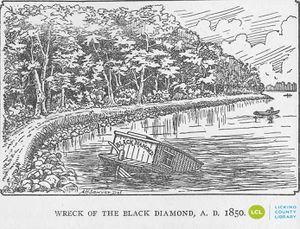

| − | + | [[File:Black diamond wreck story fo buckeye lake logo.jpg|thumb|Sketch of the wreck of the Black Diamond from ''Story of Buckeye Lake'']] Even less fortunate than the "Licking Summit" was the "Black Diamond" canal boat; while hauling coal through the reservoir that is now Buckeye Lake, the "Black Diamond" ran into one of the many stumps lurking below the water's surface, tearing a hole in the bottom of the boat. The "Black Diamond" was able to maneuver closer to the shore and the captain and crew abandoned ship, but the canal boat came to rest partially submerged near the bank with its heavy load. <ref> Simpson, J.,'' The Story of Buckeye Lake: Historical,'' (1912), 51-59. </ref> | |

| − | The decades in which the canal functioned at its height | + | The decades in which the canal functioned at its height produced industry and commerce in the towns along its banks, but also a number of stories that, even if not all accounts are true ones, intimate the rough conditions of life in towns that experienced sudden booms in population and wealth that catered to a transient population of travelers and canal men. One legend purports that the ghost of a former canal-boat captain haunts a section of South Second Street in Newark near an area once called "Gingerbread Row" and known for its saloons and petty crime. While staying in a room on the south side of Newark's square, the captain was murdered and dumped into the canal. His restless ghost still haunts the area, or so some allege. <ref> Stamper, C. “Legends of Licking County,” ''Community Booster West'', Oct. 26, 2003, 1 –3, </ref> |

| − | Another story that may | + | Another story that may relate true events was the trial of a German Immigrant accused of the murder of his wife while passing through Newark in August 1835. According to a local newspaper report, the German husband, known as "The Dutchman," allegedly threw his wife overboard causing her to drown. At his trial for murder in October of the same year, the "Dutchman" underwent a form of trial by ordeal that sufficed to determine his guilt or innocence; he was made to touch the body of his dead wife to see if the corpse underwent a supernatural reaction. Apparently there was no response and this act, called "The Touch," was enough to prove to the jury the man's innocence in his wife's death. <ref> Fleming, D. ''Six Cents and a Racoon Tail: A Collection of Short Anecdotes from 19th century Newark and Licking County'' (2007) </ref> |

| − | When the State Board of Public Works sought to make repairs on the canal in | + | When the State Board of Public Works sought to make repairs on the canal in 1899, they determined that it would be necessary to lower the water levels in the city of Newark's canal to do so. The health officer for Newark, Dr. Smith, objected, declaring that lowering the water level would be detrimental to the city's health due to the number of dead animals and quantities of refuse and garbage the citizens of Newark deposited in the canal. Noting Dr. Smith's objections, the Board undertook a thorough cleaning of the canal before repairs were made. <ref>Fleming, D. ''Six Cents and a Racoon Tail: A Collection of Short Anecdotes from 19th century Newark and Licking County.'', (2007) </ref> |

| + | Some of the best stories of Licking County come from the days of the Canal, but songs were born of the era too, used by boatmen to pass the time and lighten their work, in a manner similar to the Sea Shanties of ocean-bound ships. Learn more about one of these local Canal Shanties in our [https://youtu.be/MlvpMA7JdWk History Tidbit] video. | ||

==The Canal's Decline== | ==The Canal's Decline== | ||

| − | + | Superseded by rail in the 1850s and 60s, the Ohio-Erie Canal went into steep decline. Though in decline, the canal was still active in the last decades of the 19th century. The entire length of the system was leased by the state in 1861 to a private company which operated the waterway until 1878, when it abandoned its lease and management returned to the state. The use of the canal as a means of transport in Newark had come to an end by the 1890s. By that time, the water level was no longer consistent along stretches but rather pooled and grew stagnant. The aqueduct that once carried boats above Racoon Creek had collapsed. The Newark city council passed a series of resolutions that brought an end to the canal, letting the remaining spots be filled with earth and turned into roadways. Among the few remnants left of the canal is its name, given to the short street that runs along the lost path of the canal south of downtown Newark next to Market street, named, appropriately, Canal Street. <ref> Brister, E., ''Centennial History of the City of Newark and Licking County, Ohio'', (1909), 184 </ref> . | |

| − | + | Much of the existing canal between Newark and Hebron became paved into a modern highway in 1934. <ref> "The Vanishing Canal," ''The Newark Leader'', Apr. 26, 1934 </ref> | |

| Line 54: | Line 57: | ||

| − | For more information see | + | For more information see these items in the Licking County Library Collection: |

| − | Commencement of the Ohio Canal at the Licking Summit, July 4, 1825. Columbus: The F.J. Heer Printing Co., 1926. | + | ''Commencement of the Ohio Canal at the Licking Summit'', July 4, 1825. Columbus: The F.J. Heer Printing Co., 1926. |

| − | Scheiber, Harry N. Ohio Canal Era: A Case Study of Government and the Economy, 1820-1861. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1969. | + | Scheiber, Harry N. ''Ohio Canal Era: A Case Study of Government and the Economy, 1820-1861''. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1969. |

| + | |||

| + | Simpson, Joseph. ''The Story of Buckeye Lake: Historical'' Columbus, Ohio: The Hann and Adair Printing Co, 1912. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | J.G. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Latest revision as of 09:09, 29 June 2021

Contents

The Ohio and Erie Canal

The Ohio and Erie was an important component of early American transportation and commerce. Though it thrived in a relatively short period of time, sometimes with barely 20 years of heavy activity in the 1830s and 40s, the canals that connected the great American waterways—from the Great Lakes to the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers--permitted economic expansion and settlement of important regions of the United States in an era before the widespread use of rail. [1] The growing yet sparsely populated states West of the Appalachians and East of the Mississippi were rich in agricultural potential, but lacked the infrastructure to move goods and people quickly. A spike in the price of agricultural products in the 1820s provided the impetus to states like Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Indiana to begin ambitious canal-building projects to connect those important waterways to the towns and cities in the interior and far-flung coastal markets. After the passage of legislation on February 4, 1825, the Ohio-Erie Canal could begin construction.

The first groundbreaking took place at the Licking Summit, near Newark, on July 4th of that year. It was quickly joined by other canal construction sites in Ohio as the system's orchestrator, Alfred Kelley, sought to complete the canal as quickly as possible. Though it took 8 years of toil and just over $4 million dollars, the Ohio Canal System connected Lake Erie to the Ohio River in less time and at less cost than some of its neighboring states, finishing six months ahead of schedule in January 1833. [2] The canal that stretched 333 miles of watery highway from Cleveland to Portsmouth included 152 locks, 16 aqueducts, and 153 culverts. The aqueducts were a clever feature of Ohio's canal system, permitting the canal to pass over the many existing small streams without disturbing their natural flow.

At its peak in 1851, before the increasing competition of the railroads precipitated its decline, around 400 boats passed through the Ohio Canal System, generating about $350,000 in revenue. [3] Toll collectors along the path of the canal charged tolls and water rents to the captains based on their boat and the value of its cargo. Charges to use the canal could run two to three cents per mile and the average canal boat could carry from fifty to eighty tons of cargo in addition to crew and passengers. [4]

The massive undertaking also had a human cost; the hard-pressed canal builders, mostly Irish immigrants, suffered from low pay, poor work conditions, and outbreaks of debilitating diseases such as malaria, smallpox, and cholera. [5]

The Canal in Licking County

There were a number of canals constructed in Ohio and surrounding states during the 1820s and 1830s, and Licking County was the location of a critical stretch of the Ohio-Erie Canal, including the Licking Summit, which was the point of initial groundbreaking and, at 413 feet above the level of the Ohio River, was one of the points of highest elevation on the Canal.A boat passing from Cleveland to Portsmouth would cross the county from the center of its eastern border to exit in the southwest corner. Entering at Toboso, the canal moved west along what is now Ohio 16 to Newark. A boat would pass south of Newark's city center, near Market street or what is now Canal Street. Leaving Newark along Main St, the canal turned south along Union St. to what was once the separate village of Lockport and followed a southwestern course through what is now Heath and Ohio 79. The canal passed through Hebron and by Buckeye Lake—which would play a critical role as a reservoir—and exited the county near Millersport. Several feeder canals, or short additions to the system, were added at Kirkersville, Granville, Raccoon Creek, and the North Fork.

A groundbreaking ceremony took place in Newark on July 4th, 1825, with the Governors of Ohio and New York, as well as a number of other dignitaries, in attendance. Poor weather, a trouble-ridden presentation, and a swarm of unhelpful flies allegedly made the party less than memorable, though the speeches given to inaugurate the event were recorded for posterity in local papers. [6] .

The topography of Licking County required a special excavation in the southern part of the county. This excavation, locally referred to as the "Deep Cut," incised through a ridge of earth along three miles of the canal route. At the deepest point, the laborers dug thirty-four feet down at an average depth of twenty-four feet, creating what was one of the largest projects undertaken in the canal's construction. [7] .

The transformation of Buckeye Lake was another local consequence of the canal; reserves of water were needed to maintain water levels in the canal system, particularly at the crucial point of the Licking Summit.[8] Local water supplies were used when possible, but reservoirs and artificial lakes were used in their place if natural water systems proved insufficient. An area of shallow water and swampy wetlands along the South Fork of the Licking River, known as the "Big Swamp," was one natural geographic feature found by early European settlers and surveyors in central Ohio. This low-lying wetland, also known as the "Big Pond," became a reservoir known as the Licking County Reservoir in the 1830s with damns installed to increase the water level to a point sufficient for the use of the canal. The conversion of the area into Buckeye Lake led to increased economic activity for communities surrounding the new reservoir. [9]

One citizen of Newark, Louella Fant, gave a vivid account in 1934 of the colorful scene and expectant crowds along the canal, reminiscing of the times when a boat would pass through town: "Men lolling on top of the cabin, women, and children dressed in calico dresses and sun-bonnets, or better clad in silk, with shawls about their shoulders with dainty lace and straw bonnets kept in place by a ribbon tied under the chin, occupied the chair on the deck and held sunshades to display the up-to-date fashions, as is always the fashion. Pretty faces often appeared at the windows. Persons on board ogled the natives—called to them in banter, others 'viewed the landscape o'er' with contempt or dropped the slant of the sun shades. " [10]

There are several factual, first-hand accounts of the Ohio-Erie canal in Licking County that lend themselves to an idyllic, romantic image of the experience. The reality may have been far messier and rougher than the stories indicate. In its final years in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the canal in Newark proved to be a health hazard and open sewer.

Canal Tales

The first canal boat built south of Cleveland may have been built in Licking County. E.M. P. Brister, in his Centennial History of the City of Newark and Licking County, Ohio, credited the Troy and Ohio Line and the supervision of a Mr. Wallace with the construction of a boat at the warehouse built on the Granville feeder canal. [11] .

"The Licking Summit " was another canal boat built in Licking County, whose story survives due to its spectacular failure as a working boat; constructed in Hebron as an investment venture by local businessman led by Joshua Smith, the "Summit" set out on its maiden voyage on July 4th, 1828 to great fanfare. Much to the chagrin of the owners and passengers, the "Summit" ran aground a few times on that first trip, and once it reached the gates of the lock at the Licking Summit, the boat proved too wide to pass through the canal locks. Unable to function as a canal boat, the "Summit" returned to Hebron where it remained tied in place on the water and became used as a saloon, and--allegedly--a house of prostitution. [12] The boat may also have been called "The Lady Jane" at some point during its existence. Joseph Simpson, who collected a number of stories along with his first-hand accounts in The Story of Buckeye Lake, claimed the "Lady Jane" as the original name of the boat and provided a story that mirrors other accounts. [13]

Even less fortunate than the "Licking Summit" was the "Black Diamond" canal boat; while hauling coal through the reservoir that is now Buckeye Lake, the "Black Diamond" ran into one of the many stumps lurking below the water's surface, tearing a hole in the bottom of the boat. The "Black Diamond" was able to maneuver closer to the shore and the captain and crew abandoned ship, but the canal boat came to rest partially submerged near the bank with its heavy load. [14]The decades in which the canal functioned at its height produced industry and commerce in the towns along its banks, but also a number of stories that, even if not all accounts are true ones, intimate the rough conditions of life in towns that experienced sudden booms in population and wealth that catered to a transient population of travelers and canal men. One legend purports that the ghost of a former canal-boat captain haunts a section of South Second Street in Newark near an area once called "Gingerbread Row" and known for its saloons and petty crime. While staying in a room on the south side of Newark's square, the captain was murdered and dumped into the canal. His restless ghost still haunts the area, or so some allege. [15]

Another story that may relate true events was the trial of a German Immigrant accused of the murder of his wife while passing through Newark in August 1835. According to a local newspaper report, the German husband, known as "The Dutchman," allegedly threw his wife overboard causing her to drown. At his trial for murder in October of the same year, the "Dutchman" underwent a form of trial by ordeal that sufficed to determine his guilt or innocence; he was made to touch the body of his dead wife to see if the corpse underwent a supernatural reaction. Apparently there was no response and this act, called "The Touch," was enough to prove to the jury the man's innocence in his wife's death. [16]

When the State Board of Public Works sought to make repairs on the canal in 1899, they determined that it would be necessary to lower the water levels in the city of Newark's canal to do so. The health officer for Newark, Dr. Smith, objected, declaring that lowering the water level would be detrimental to the city's health due to the number of dead animals and quantities of refuse and garbage the citizens of Newark deposited in the canal. Noting Dr. Smith's objections, the Board undertook a thorough cleaning of the canal before repairs were made. [17]

Some of the best stories of Licking County come from the days of the Canal, but songs were born of the era too, used by boatmen to pass the time and lighten their work, in a manner similar to the Sea Shanties of ocean-bound ships. Learn more about one of these local Canal Shanties in our History Tidbit video.

The Canal's Decline

Superseded by rail in the 1850s and 60s, the Ohio-Erie Canal went into steep decline. Though in decline, the canal was still active in the last decades of the 19th century. The entire length of the system was leased by the state in 1861 to a private company which operated the waterway until 1878, when it abandoned its lease and management returned to the state. The use of the canal as a means of transport in Newark had come to an end by the 1890s. By that time, the water level was no longer consistent along stretches but rather pooled and grew stagnant. The aqueduct that once carried boats above Racoon Creek had collapsed. The Newark city council passed a series of resolutions that brought an end to the canal, letting the remaining spots be filled with earth and turned into roadways. Among the few remnants left of the canal is its name, given to the short street that runs along the lost path of the canal south of downtown Newark next to Market street, named, appropriately, Canal Street. [18] .

Much of the existing canal between Newark and Hebron became paved into a modern highway in 1934. [19]

For more information see these items in the Licking County Library Collection:

Commencement of the Ohio Canal at the Licking Summit, July 4, 1825. Columbus: The F.J. Heer Printing Co., 1926.

Scheiber, Harry N. Ohio Canal Era: A Case Study of Government and the Economy, 1820-1861. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1969.

Simpson, Joseph. The Story of Buckeye Lake: Historical Columbus, Ohio: The Hann and Adair Printing Co, 1912.

J.G.

References

- ↑ Coleman, R., "Once a Great Notion," Ohio, (August 1988), 18

- ↑ Coleman, R., "Once a Great Notion," Ohio, (August 1988), 23-24

- ↑ Jones, L., "Trace the Path of the 'big ditch'", Community Booster East, Jul. 20, 2003, 9

- ↑ Brister, E., Centennial History of the City of Newark and Licking County, Ohio, (1909), 183

- ↑ Pressler, C., "The Ohio Canal," The Advocate, Nov. 6, 1983. For a counter to the poor pay and work conditions see Brister, E., Centennial History of the City of Newark and Licking County, Ohio, (1909), 178-179.

- ↑ Pressler, C., "The Ohio Canal," The Advocate, Nov. 6, 1983

- ↑ Brister, E., Centennial History of the City of Newark and Licking County, Ohio, (1909), 179

- ↑ Pressler, C., "The Ohio Canal," The Advocate, Nov. 6, 1983

- ↑ Hall, L., The Advocate, Feb. 12, 1984

- ↑ Jones, B., "Our County History," The Advocate, Mar 5, 1934

- ↑ Brister, E., Centennial History of the City of Newark and Licking County, Ohio, (1909), 183

- ↑ Hill, N., History of Licking County, 598; Pressler, C., "The Ohio Canal," The Advocate, Nov. 6, 1983

- ↑ Simpson, J. The Story of Buckeye Lake: Historical, (1912), 35-38

- ↑ Simpson, J., The Story of Buckeye Lake: Historical, (1912), 51-59.

- ↑ Stamper, C. “Legends of Licking County,” Community Booster West, Oct. 26, 2003, 1 –3,

- ↑ Fleming, D. Six Cents and a Racoon Tail: A Collection of Short Anecdotes from 19th century Newark and Licking County (2007)

- ↑ Fleming, D. Six Cents and a Racoon Tail: A Collection of Short Anecdotes from 19th century Newark and Licking County., (2007)

- ↑ Brister, E., Centennial History of the City of Newark and Licking County, Ohio, (1909), 184

- ↑ "The Vanishing Canal," The Newark Leader, Apr. 26, 1934