Difference between revisions of "Johnny Clem"

(→Memorials) |

(→Memorials) |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

==Memorials== | ==Memorials== | ||

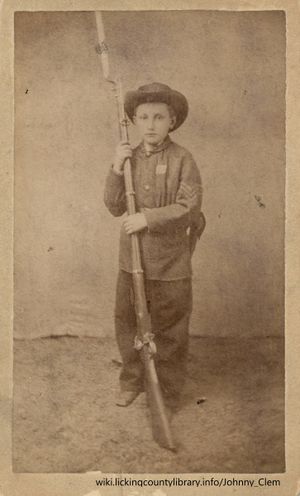

| − | [[File:Johnny_Clem_Statue. | + | [[File:Johnny_Clem_Statue.jpeg|thumb|alt=A photo of the statue of Johnny Clem.|Statue of Johnny Clem in Veterans' Park, Newark]] |

*In 1959, John L. Clem Elementary School, at 475 Jefferson Road in Newark, was dedicated to Clem’s memory and named in his honor.<ref>Kohser, “John Clem: Newark’s Own Civil War Hero.”</ref> | *In 1959, John L. Clem Elementary School, at 475 Jefferson Road in Newark, was dedicated to Clem’s memory and named in his honor.<ref>Kohser, “John Clem: Newark’s Own Civil War Hero.”</ref> | ||

Revision as of 12:19, 31 August 2017

Major General John Lincoln Clem was born on August 13, 1851[1] at a house located at 26 W. Harrison Street in Newark, Ohio.[2] Clem was christened as John Joseph Klem at St. Francis de Sales Catholic Church. He changed the spelling of his last name to Clem, which he preferred over the original spelling of Klem, and he changed his middle name to Lincoln during the Civil War.[3] Clem explained that he met Abraham Lincoln once in 1864 and liked him so much that he decided to take his name.[4] “Johnny” Clem, as he is widely referred to, is known as the “Drummer Boy of Chickamauga,” and is commonly regarded as being the youngest person to bear arms in the Civil War . Clem died at the age of 85 on May 13, 1937 in San Antonio, Texas. [5]

Contents

Early Life

Clem was born to Roman and Magdalene Klem in 1851.[6] The family had been staying in the home of Clem’s late uncle, Peter Kline, who passed away approximately five weeks before Johnny was born. Johnny Clem’s mother and father moved into the home to assist Kline’s widow , who was caring for their six children. It was in this house that Johnny Clem was born on August 13, 1851.[7]

In May of 1861, Clem’s mother, Magdalene, was killed by a train while trying to cross Railroad Street in Newark. Clem described the event as life changing, saying, “Life was never quite the same after my mother died.”[8]

Service in the Civil War

Within weeks of his mother’s death, Johnny Clem ran away from home. Clem, who was not yet 10 years old, attempted to join the 3rd Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry.[9] However, due to his age and his size, he was rejected. Instead of simply going home, Clem hopped aboard a train that was transporting the regiment. He stayed hidden aboard a baggage car until he arrived with the regiment at its destination of Camp Dennison in Cincinnati , Ohio. Clem’s father, Roman, went to Cincinnati to retrieve his son, but Johnny was able to evade him.[10]

At Camp Dennison, Clem tried to enlist, but was unable to due to his young age. The officers, however, did allow him to stay with them at the camp. The men took Clem in and provided him with food and wages, giving him the role of drummer boy.[11]

Johnny Clem marched with the 22nd Regiment Michigan Infantry on the battlefield, although he was not actually enlisted, on April 6, 1862 at the Battle of Shiloh at Pittsburgh Landing, Tennessee. While at Shiloh, Clem’s drum was destroyed by a piece of shrapnel. He narrowly escaped serious injury. For his bravery, he was dubbed “Johnny Shiloh.” [12]

Clem’s most famous Civil War involvement took place during the Battle of Chickamauga in September of 1863. In the midst of battle, Johnny became separated from the rest of the men. Clem was discovered by a Confederate colonel and threatened to surrender. Quickly, Clem fired his musket at the colonel, shooting him from his horse. Clem was able to escape, making his way to Chattanooga where he reunited with Union forces. For his bravery, Clem was made a sergeant at just 12 years old.[13][14] It was as a result of this event that Clem earned his nickname “The Drummer Boy of Chickamauga.” [15]

In October of 1863, Clem was captured by Confederate forces and paraded as an example of the Union’s desperation in the war, resorting to using a child. Clem was paroled and sent back to Ohio. The following January, in 1864, Clem returned to active duty as a mounted orderly in service to Major General Thomas.[16]

Life after the Civil War

After the end of the Civil War in 1864, Johnny Clem returned home to Newark. Clem returned to school and graduated from Newark High School in 1870.[17] Clem was readmitted into the army in 1871, commissioned as a second lieutenant. [18]

Clem married Anita French in 1875, and the couple had six children, five of which passed away before adulthood. Clem continued serving in the military, serving in the Philippines and the Spanish American War. At the end of his career, Clem had reached the rank of Major General.[19]

For the last year of his life, Clem’s health deteriorated. He was confined to his home for the final six months of his life. On May 13, 1937, John Clem passed away at his home in San Antonio, Texas.[20] He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. [21]

Controversy

Throughout the years, there have been claims that Clem falsified his accounts of his military service, or that he was not the youngest person to enlist during the Civil War. In September of 1907, an article was published in the Newark American Tribune claiming that Clem was not, in fact, the youngest person to fight in the Civil War. According to the article, Clem was neither the youngest nor the second youngest. The article, entitled, “Well, Not Eli, but Johnny Was Second Youngest” awards the honor of youngest enlisted soldier in the Civil War to Alfred C. White, who was also born in Newark. According to the article, White was born in 1853 and enlisted as a drummer boy in Company D of the 64th Ohio Volunteer Infantry in 1861. The article claims that the second youngest enlisted soldier was Eli Wright, of Youngstown, Ohio. Wright enlisted when he was 12 years old.[22] Although Clem was not commissioned until after the Battle of Chickamauga, when he was 12 years old, he attached himself to the 22nd Regiment Michigan Infantry at just 10 years old.

Clem’s record again came into question in 1989 after Civil War researcher Greg Pavelka wrote an article in the Civil War Times Illustrated claiming Clem had never fought at Shiloh at all, and that he couldn’t have served with the 22nd Michigan.[23] A mock trial was set for October 14, 1989 at the Licking County Courthouse. Arguing the case against Clem was Pavelka, while Clem was defended by biographer Dean Jauchius, who co-authored the 1959 novel Johnny Shiloh.[24] The trial drew hundreds to the Courthouse, bringing a new awareness of Clem and his accomplishments. The final verdict – not guilty. The jury found that Clem had not falsified his claims of fighting at Shiloh and hadn’t lied about any other details of his military career.[25]

Memorials

- In 1959, John L. Clem Elementary School, at 475 Jefferson Road in Newark, was dedicated to Clem’s memory and named in his honor.[26]

- On November 6, 1997, Clem was inducted into the Ohio Veterans Hall of Fame by Governor George Voinovich. [27]

- In 1999, Mike Major, a sculptor from Urbana, Ohio, was selected to create a 6-foot statue of Clem to be placed in Veterans’ Park in Newark. Major won the bid to create the bronze statue at a cost of $73,230. [28] The statue can be seen in the park at the corner of West Main Street and Sixth Street in Newark.

C.S.

References

- ↑ Nina Kohser, “John Clem: Newark’s Own Civil War Hero,” The Newark Advocate, June 10, 1984.

- ↑ Amy Hollon, “Legend’s Newark Roots Confirmed,” The Advocate, February 3, 2009.

- ↑ Kathy Wesley, “Johnny Clem a Hero – Or Was He?,” The Newark Advocate, October 11, 1989, 1.

- ↑ “General Clem Dies in Texas Home,” The Newark Advocate American Tribune, May 14, 1937, 1.

- ↑ Wesley, “Johnny Clem a Hero – Or Was He?”

- ↑ Kohser, “John Clem: Newark’s Own Civil War Hero.”

- ↑ Hollon, “Legend’s Newark Roots Confirmed.”

- ↑ Kohser, “John Clem: Newark’s Own Civil War Hero.”

- ↑ Wesley, “Johnny Clem a Hero – Or Was He?”

- ↑ Kohser, “John Clem: Newark’s Own Civil War Hero.”

- ↑ Kohser, “John Clem: Newark’s Own Civil War Hero.”

- ↑ Kohser, “John Clem: Newark’s Own Civil War Hero.”

- ↑ Kohser, “John Clem: Newark’s Own Civil War Hero.”

- ↑ Jim Lukens, Clem Became a Legend in Civil War,” ThisWeek in Licking County, May 22, 2005.

- ↑ “General Clem Dies in Texas Home,” 1.

- ↑ Wesley, “Johnny Clem a Hero – Or Was He?”

- ↑ “General Clem Dies in Texas Home,” 7.

- ↑ Wesley, “Johnny Clem a Hero – Or Was He?”

- ↑ Kohser, “John Clem: Newark’s Own Civil War Hero.”

- ↑ “General Clem Dies in Texas Home,” 1.

- ↑ Kohser, “John Clem: Newark’s Own Civil War Hero.”

- ↑ “Well, Not Eli, but Johnny Was Second Youngest,” Newark American Tribune, September 4, 1907.

- ↑ Wesley, “Johnny Clem a Hero – Or Was He?”

- ↑ “Excitement Builds for Unique ‘Trial’ of War Hero Clem,” The Licking Countian, October 12, 1989.

- ↑ David Jacobs, “Johnny Shiloh’s Name Cleared,” The Columbus Dispatch, October 15, 1989

- ↑ Kohser, “John Clem: Newark’s Own Civil War Hero.”

- ↑ Sean Rorke, “Newark’s Johnny Clem Joins Veterans Hall of Fame,” The Advocate, November 2, 1997.

- ↑ Susan Parker Geier, “Drummer Boy …Finds a Place in the Park,” The Advocate, February 19, 1999.