Difference between revisions of "Prehistory of Licking County"

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

The stones however were debunked in 1867, shorting following Wyrick's death. When a close friend of Wyrick's, a Dr. McCarty, was going through his estate he found an Old Hebrew Bible and a chest of stone cutting tools among his possessions. He informed archeology expert Charles Whittlesey, who published an article in 1872 declaring Wyrick and the Holy Stones to be a fraud. <ref name=stones1> </ref> Three more Hebrew stones were discovered in the area, two on a farm in Licking County in 1865 and another in mound near Wyrick's original excavation location further south in 1867. <ref> Wesley, K. (1990, June 6). Newark Holy Stones. The Newark Advocate. </ref> Skeptics remain on both sides of the argument, debating the authenticity of Wyrick and the Holy Stones. | The stones however were debunked in 1867, shorting following Wyrick's death. When a close friend of Wyrick's, a Dr. McCarty, was going through his estate he found an Old Hebrew Bible and a chest of stone cutting tools among his possessions. He informed archeology expert Charles Whittlesey, who published an article in 1872 declaring Wyrick and the Holy Stones to be a fraud. <ref name=stones1> </ref> Three more Hebrew stones were discovered in the area, two on a farm in Licking County in 1865 and another in mound near Wyrick's original excavation location further south in 1867. <ref> Wesley, K. (1990, June 6). Newark Holy Stones. The Newark Advocate. </ref> Skeptics remain on both sides of the argument, debating the authenticity of Wyrick and the Holy Stones. | ||

| − | The stones are exhibited at the Johnson-Humrickhouse Museum in Coshocton, Ohio. | + | The stones are exhibited at the Johnson-Humrickhouse Museum in Coshocton, Ohio. <ref> Wesley, K. (1991, July 18). 'Newark Holy Stones' going on display in Coshocton. The Newark Advocate. </ref> |

===Mastadon=== | ===Mastadon=== | ||

Revision as of 13:26, 30 March 2015

The history of Licking County begins nearly 14,000 years ago when the area was still covered by a giant glacier. [1] Near the end of the last Ice Age, the glacier began to retreat and Ohio's climate grew warm and greenery began to takeover the area. During that time, animals wandered into the area, including mastodons, giant beavers and sloths, and saber toothed cats, searching for food. Soon after, the first people came to inhabit the area called Paleoindians, named by scientists to mean really old Indians. [1] These Paleoindians were hunters who survived by hunting and following the herds of animals as they settled across Ohio. They hunted with spear like weapons called atlatl. The Paleoindian culture dominated the area for nearly 6,000 years while the climate continued to grow warmer still. [1]

The history of county picks back up again about 2000 years ago when the area was occupied by the Hopewell Indians. They lived on the land for a number of years, before disappearing for no apparent reason. They left behind a countless number of mounds in the Great Circle, the largest named Earthworks. [2] Ohio is reported to contain more remains of the Mound Builders than any other state, with Licking County being one of the most prominent locations. After the Hopewell Indians came the Wyandotte, Shawnee and Delaware Indians who settled in the area. It is believed that it was during this time that Licking County got it's name from the salt licks that littered the banks of the river.

Soon after, English settlers from the east came to explore the area. Christopher Gist was the first white man to set foot in Licking County in 1751. [3] He came as a member of the Ohio Company of Virginia, and crossed the Licking River near the mouth of Bowling Green Run, about four miles east of Newark. After the came John H. Phillips, and his two younger brothers, and Thomas and Eramus, immigrants from Wales. John H. was supposedly skirting the law, and left the country to avoid arrest. Together the men purchased 2000 acres of land in the northeast corner, now Granville. Two other early settlers, Elias Hughes and John Ratliff brought their families to settle in the Bowling Green region, east of present day Newark in 1798. [4] Newark was the first permanent settlement in Licking County established in 1802.

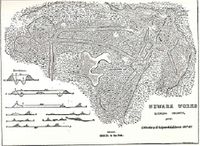

Earthworks

Located in the western part of Newark, the Newark Earthworks are the largest geometric earthworks in the world. [5] They were built by the Hopewell Indians between 100 B.C. and A.D. 400, and are the only remaining evidence of the Moundbuilders Indians in Licking County. The geometric enclosures were once part of an elaborate system that spread over four miles, connected by embankment lined paths. The specific purpose for the earthworks is not specifically known, but scientists speculate that they were used for burials or ceremonial rituals. [6] The mounds measure 1200 feet in diameter, encloses 30 acres and rises 12 feet above the average level of the ground it encloses. At the center lies Eagle Mound, a series of conjoined mounds.

The mound was discovered by Isaac Stadden, an early settler of Licking County, around 1800. [7]

Artifacts

Holy Stones

The Holy Stones were discovered by David Wyrick, a Licking County surveyor, near ancient burial grounds of Moundbuilders Indians at the Newark Earthworks in June 1860. The stone Wyrick discovered was a five inch long smoothly polished, reddish keystone, with strange markings engraved on the flat sides. [8] Rev. Matthew Miller identified the stone as a Jewish teraphim, and the pointed end was intended to indicate the direction of hidden material. The inscribed markings were Hebrew that read:

- The King of the Earth

- The Word of the Lord

- The Laws of Jehovah

- The Holy of Holies [8]

The major significance of the stones and the inscriptions came from the belief that these stone came from the lost tribes of Israel, and that the Moundbuilders were themselves descendants of the lost Israelites. It also gave proof that the Israelites made their way through Asia and crossed into North America. A few months later later in November, further discoveries were made in a mound about 7 miles south of Newark. There, Wyrick found a further a wooden sarcophagus and a ovoid stone, [8] also with Hebrew markings that were part of the Ten Commandments or Decalogue. [9] By 1863 the stones had become famous and were made part of special exhibits.

The stones however were debunked in 1867, shorting following Wyrick's death. When a close friend of Wyrick's, a Dr. McCarty, was going through his estate he found an Old Hebrew Bible and a chest of stone cutting tools among his possessions. He informed archeology expert Charles Whittlesey, who published an article in 1872 declaring Wyrick and the Holy Stones to be a fraud. [8] Three more Hebrew stones were discovered in the area, two on a farm in Licking County in 1865 and another in mound near Wyrick's original excavation location further south in 1867. [10] Skeptics remain on both sides of the argument, debating the authenticity of Wyrick and the Holy Stones.

The stones are exhibited at the Johnson-Humrickhouse Museum in Coshocton, Ohio. [11]

Mastadon

Flint Ridge

Where is Flint Ridge?

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Hite, A. (1997, February 6). Prehistoric People of Ohio and Licking County. Ace News.

- ↑ Rutter, C. (2008). A Brief History of Licking County. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ↑ Rutter, C. (2008, January 1). A Brief History of Licking County. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ↑ Hall, L. (1983, October 23). On land where buffaloes once roamed, early settlers founded town of Newark. The Newark Advocate, p. 1D.

- ↑ Stare, F. (2002, February 10). Newark, Licking County home of many firsts. The Newark Advocate.

- ↑ Ohio Historical Society, (1993). The Newark Earthworks. Columbus, Ohio.

- ↑ The Ancient Mounds In and Around the City of Newark Ohio. (1964, April 24). The Newark Chamber of Commerce.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Arter, B. (1958, November 16). The Holy Stones of Newark. The Columbus Dispatch.

- ↑ Westall, B. (1982, January 20). 'Holy Stones' mystery survives. The Newark Advocate, p. 13.

- ↑ Wesley, K. (1990, June 6). Newark Holy Stones. The Newark Advocate.

- ↑ Wesley, K. (1991, July 18). 'Newark Holy Stones' going on display in Coshocton. The Newark Advocate.